How the Teenage Brain Responds in Social Situations

by Jason von Stietz - February 11, 2015

How does the teenage brain react when seeing a friend? How about a stranger? What happens to the brain when viewing Facebook? Researchers have studied how the brain responds in social situation, in daily life and online. Amanda Baker discusses the responses of the teenage brain in a recent article in Scientific American:

While we all may vary on just how much time we like spending with other people, humans are overall very social beings. Scientists have already found this to be reflected in our health and well-being – with social isolation being associated with more depression, worse health, and a shorter life. Looking even deeper, they find evidence of our social nature reflected in the very structure of our brains.

Just thinking through your daily interactions with your friends or siblings probably gives you dozens of examples of times when it was important to interpret or predict the feelings and behaviors of other people. Our brains agree. Over time parts of our brains have been developed specifically for those tasks, but apparently not all social interaction was created equally.

When researchers study the brains of people trying to predict the thoughts and feelings of others, they can actually see a difference in the brain activity depending on whether that person is trying to understand a friend versus a stranger. Even at the level of blood flowing through your brain, you treat people you know well differently than people you don’t.

These social interactions also extend into another important area of the brain: the nucleus accumbens. This structure is key in the reward system of the brain, with activity being associated with things that leave you feeling good. Curious if this could have a direct connection with behavior, one group of scientists studied a very current part of our behavior as modern social beings: Facebook use.

The researchers had a group participants record short videos about themselves. The participants believed that these videos would be viewed by anonymous reviewers who would then pick 10-15 adjectives describing their perception of the participant. The next day, participants were placed in an MRI and the nucleus accumbens was monitored while they heard two sets of adjectives: those selected by reviewers to describe the participant and those selected to describe one of the other participants.

In reality, the adjectives had been pre-selected by the researchers, allowing them measure activity in the nucleus accumbens when the participant heard that the reviewers thought highly of them and compare it to activity while they heard that the reviewers thought highly of the other participant.

The researchers found that the participants whose brains gave a bigger reward for their own feedback compared to the feedback of others were more likely to use Facebook more intensely. Considering that Facebook allows for personal feedback in the form of likes and comments, as well as the ability to monitor the success and approval of others, this correlation seems to make sense.

Differences in these parts of the brain can account for some variability between individuals, but what about differences that seem to be defined by age?

Many areas of the brain grow and develop as you age, and the areas responsible for social emotions are no different. Between the ages of four and five, you start to develop the ability to understand that people around you could be having thoughts or emotions that are different than your own. Further important changes occur during a period that society often seems to single out as the pinnacle for being different: adolescence.

Adolescence – the period extending from puberty to the point of independent stability – is often portrayed as a very dramatic time with a new emphasis placed on the importance of friendships and social input. Researchers have even found during this period that many adolescents value the input of their peers even over the input of their family.

The current generation of teens are faced with the addition of social media and digital content to their lives, additions which seem to have pushed many age-driven differences in behavior into a new arena. There are even notable differences in the way the current generation of teens consumes media. While older adults watch ~47 hours per week of television on average, current teens are only watching about 19 hours. Instead, they are consuming vast amounts of online video – like Youtube, Vine, and vlogs.

In traditional television or movies the stars and the plots are often mysterious people and ideas that cannot be touched by the outside world. In contrast, young vloggers and stars of Youtube and Vine often host Q&A sessions with their fans; integrate feedback into future content; and express their gratitude not to their fans, but to their “6 million friends.”

Move up just a few years to young adults and there is already a shift, with this group watching five times as much television as online video. At least some part of that difference can perhaps be accounted for with changes that occur in this period to the brain itself.

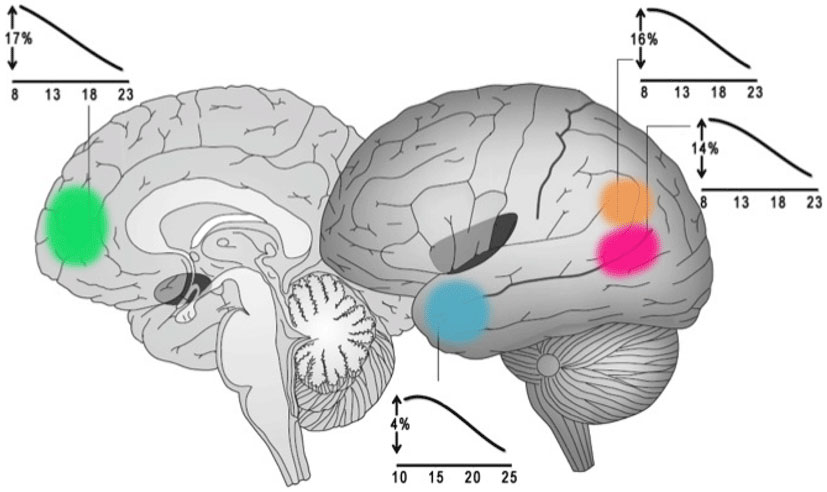

One of the areas going through important structural changes in this period – with additions of gray matter and changes in shape – is the area that deals with “social emotions.” Social emotions are those that require you to consider what others might be thinking – like guilt or embarrassment – rather than your own emotional experience – like fear. When researchers ask adolescents and adults to explain certain emotions, both groups feel and describe them in the same way. But the activity that is happening in the brain, and the way that information is being processed, differs between the two groups.

Another group of researchers wanted to understand how these differences in brain processing might eventually translate in to feelings or behavior. They set up a virtual game in which participants got to play catch with two other onscreen characters. At some point during the game the other two characters begin just to throw to each other, excluding the participant from the game. The adolescents reported more anxiety and negative feelings at being excluded than the older participants.

Because some of the brain areas still growing during adolescence include those involved with social emotions, researchers would like to know if this could lead to additional importance being assigned to those signals – the approval and disapproval of your peers – than later in life. These researchers highlight the role that this could be playing in decision-making processes. Consider that two people could see the same risks and rewards in a decision – such as smoking a cigarette. By changing the value assigned to one of these factors, such as the social outcomes, one could tip the decision in one direction or the other. If the development of the social-emotion processing in the brain causes more attention or importance to be assigned to those emotions during that period, the social outcomes could seem more extreme in their potential risk or reward in the adolescent brain.

As we learn more about the way our brains process social information and emotions, we can better understand the differences between individuals and between age groups. But as technology continues to develop, providing new social arenas and sources of feedback and comparison, we are faced with new expressions of these differences in behavior. With six billion hours of Youtube being consumed every month, it is not just scientists who are trying to understand these behaviors, but advertisers and media companies. It will be exciting to see how things change as the current generation of teens grows up.

Read the original article Here

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS