Blog

- Strategy-Based Training Might Help Mild Cognitive Impairment

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- June 26, 2016

-

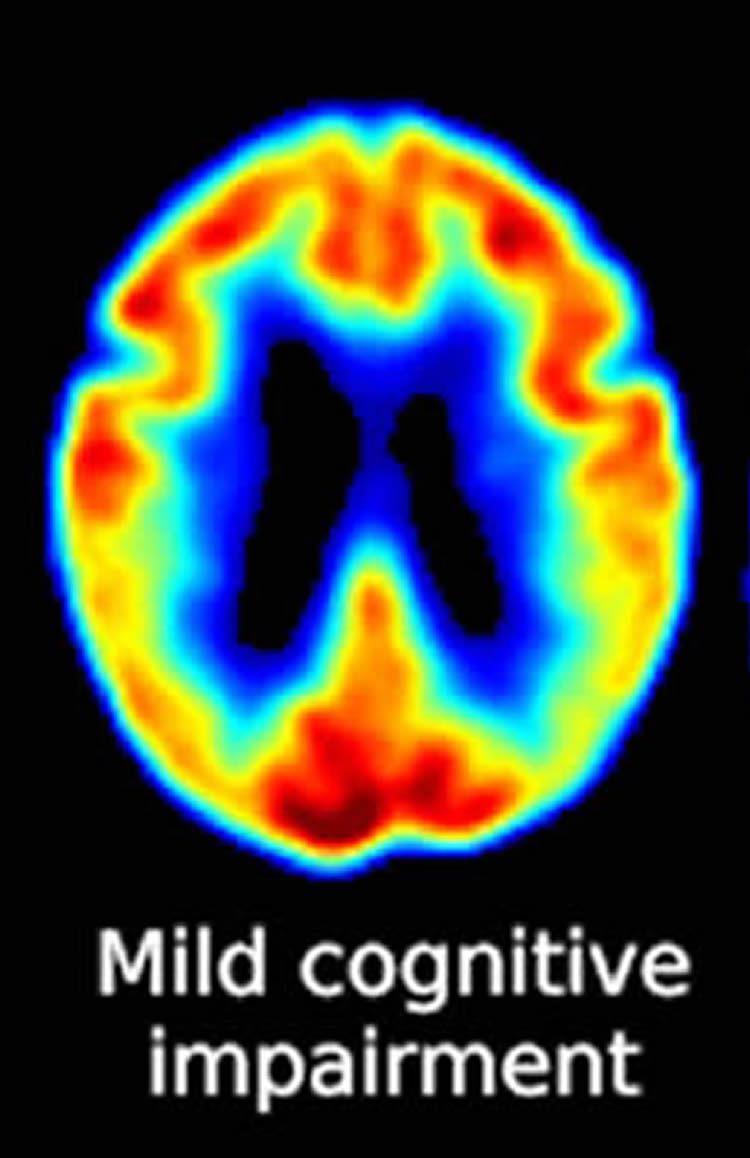

Photo Credit: Neuroscience News Making sense of everyday spoken and written language is an ongoing daily challenge for individuals with mild cognitive impairment, who are in a preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas and the University of Illinois at Urbana Champagne investigated the usefulness of strategy-based reasoning training in improving cognitive ability. The study was discussed in a recent article in Neuroscience News:

“Changes in memory associated with MCI are often disconcerting, but cognitive challenges such as lapses in sound decision-making and judgment can have potentially worse consequences,” said Dr. Sandra Bond Chapman, founder and chief director at the Center for BrainHealth and Dee Wyly Distinguished University Professor in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. “Interventions that mitigate cognitive deterioration without causing side effects may provide an additive, safe option for individuals who are worried about brain and memory changes.”

For the study, 50 adults ages 54-94 with amnestic MCI were randomly assigned to either a strategy-based, gist reasoning training group or a new-learning control group. Each group received two hour-long training sessions each week. The gist reasoning group received and practiced strategies on how to absorb and understand complex information, and the new-learning group used an educational approach to teach and discuss facts about how the brain works and what factors influence brain health.

Strategies in the gist reasoning training group focused on higher-level brain functions such as strategic attention — the ability to block out distractions and irrelevant details and focus on what is important; integrated reasoning — the ability to synthesize new information by extracting a memorable essence, pearl of wisdom, or take-home message; and innovation — the ability to appreciate diverse perspectives, derive multiple interpretations and generate new ideas to solve problems.

Pre- and post-training assessments measured changes in cognitive functions between the two groups. The gist reasoning group improved in executive function (i.e., strategic attention to recall more important items over less-important ones) and memory span (i.e., how many details a person can hold in their memory after one exposure, such as a phone number). The new learning group improved in detail memory (i.e., a person’s ability to remember details from contextual information). Those in the gist reasoning group also saw gains in concept abstraction, or an individual’s ability to process and abstract relationships to find similarities (e.g., how are a car and a train alike).

“Our findings support the potential benefit of gist reasoning training as a way to strengthen cognitive domains that have implications for everyday functioning in individuals with MCI,” said Dr. Raksha Mudar, study lead author and assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “We are excited about these preliminary findings, and we plan to study the long-term benefits and the brain changes associated with gist reasoning training in subsequent clinical trials.”

“Extracting sense from written and spoken language is a key daily life challenge for anyone with brain impairment, and this study shows that gist reasoning training significantly enhances this ability in a group of MCI patients,” said Dr. Ian Robertson, T. Boone Pickens Distinguished Scientist at the Center for BrainHealth and co-director of The Global Brain Health Initiative. “This is the first study of its kind and represents a very important development in the growing field of cognitive training for age-related cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders.”

“Findings from this study, in addition to our previous Alzheimer’s research, support the potential for cognitive training, and specifically gist reasoning training, to impact cognitive function for those with MCI,” said Audette Rackley, head of special programs at the Center for BrainHealth. “We hope studies like ours will aid in the development of multidimensional treatment options for an ever-growing number of people with concerns about memory in the absence of dementia.”

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- Regular Exercise Protects Cognition in Older Adults

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- June 17, 2016

-

Photo Credit: Getty Images As baby boomers continue to age, the need for methods of maintaining cognitive abilities in older adults continues to grow. Researchers at the University of Melbourne found that regular exercise is the most effective approach to preventing cognitive decline. Consistent exercise in any form, even as simple as walking, led to cognitive benefits. The study was discussed in a recent article in Medical Xpress:

University of Melbourne researchers followed 387 Australian women from the Women's Healthy Ageing Project for two decades. The women were aged 45 to 55-years-old when the study began in 1992.

The research team made note of their lifestyle factors, includingexercise and diet, education, marital and employment status, number of children, mood, physical activity and smoking.

The women's' hormone levels, cholesterol, height, weight, Body Mass Index and blood pressure were recorded 11 times throughout the study. Hormone replacement therapy was factored in.

They were also asked to learn a list of 10 unrelated words and attempt to recall them half an hour later, known as an Episodic Verbal Memory test.

When measuring the amount of memory loss over 20 years, frequent physical activity, normal blood pressureand high good cholesterol were all strongly associated with better recall of the words.

Study author Associate Professor Cassandra Szoeke, who leads the Women's Healthy Ageing Project, said once dementia occurs, it is irreversible. In our study more weekly exercise was associated with better memory.

"We now know that brain changes associated with dementia take 20 to 30 years to develop," Associate Professor Szoeke said.

"The evolution of cognitive decline is slow and steady, so we needed to study people over a long time period. We used a verbal memory test because that's one of the first things to decline when you develop Alzheimer's Disease."

Regular exercise of any type, from walking the dog to mountain climbing, emerged as the number one protective factor against memory loss. Asoc Prof Szoeke said that the best effects came from cumulative exercise, that is, how much you do and how often over the course of your life.

"The message from our study is very simple. Do more physical activity, it doesn't matter what, just move more and more often. It helps your heart, your body and prevents obesity and diabetes and now we know it can help your brain.

It could even be something as simple as going for a walk, we weren't restrictive in our study about what type."

But the key, she said, was to start as soon as possible.

"We expected it was the healthy habits later in life that would make a difference but we were surprised to find that the effect of exercise was cumulative. So every one of those 20 years mattered.

"If you don't start at 40, you could miss one or two decades of improvement to your cognition because every bit helps. That said, even once you're 50 you can make up for lost time."

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- Depression in Low SES Adolescents Linked to Epigenetics

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- June 7, 2016

-

Photo Credit: Getty Images Research findings have long pointed to the link between poverty and depression in high-risk adolescents. Findings by researchers at Duke University identified one mechanism involving epigenetic modification of gene expression. These epigenetic changes resulted in adolescents with more active amygdala’s, which led to higher rates of depression. The study was discussed in a recent article in Medical Xpress:

The results are part of a growing body of work that may lead to biological predictors that could guide individualized depression-prevention strategies.

Adolescents growing up in households with lower socioeconomic statuswere shown to accumulate greater quantities of a chemical tag on a depression-linked gene over the course of two years. These "epigenetic" tags work by altering the activity of genes. The more chemical tags an individual had near a gene called SLC6A4, the more responsive was their amygdala—a brain area that coordinates the body's reactions to threat—to photographs of fearful faces as they underwent functional MRI brain scans. Participants with a more active amygdala were more likely to later report symptoms of depression.

"This is some of the first research to demonstrating that low socioeconomic status can lead to changes in the way genes are expressed, and it maps this out through brain development to the future experience of depression symptoms," said the study's first author Johnna Swartz, a Duke postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Ahmad Hariri, a Duke professor of psychology and neuroscience.

Adolescence is rarely an easy time for anyone. But growing up in a family with low socioeconomic status or SES—a metric that incorporates parents' income and education levels—can add chronic stressors such as family discord and chaos, and environmental risks such as poor nutrition and smoking.

"These small daily hassles of scraping by are evident in changes that build up and affect children's development," Swartz said.

The study included 132 non-Hispanic Caucasian adolescents in the Teen Alcohol Outcomes Study (TAOS) who were between 11 and 15 years old at the outset of the study and came from households that ranged from low to high SES. About half of the participants had a family history of depression.

"The biggest risk factor we have currently for depression is a family history of the disorder," said study co-author Douglas Williamson, principal investigator of TAOS and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke. "Our new work reveals one of the mechanisms by which such familial risk may be manifested or expressed in a particular group of vulnerable individuals during adolescence."

The group's previous work, published last year in the journal Neuron, had shown that fMRI scan activity of the amygdala could signal who is more likely to experience depression and anxiety in response to stress several years later. That study included healthy college-aged participants of Hariri's ongoing Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS), which aims to link genes, brain activity, and other biological markers to a risk for mental illness.

This study asked whether higher activity in the same brain area could predict depression in the younger, at-risk TAOS participants. Indeed, about one year later, these individuals (now between 14 and 19 years of age) were more likely to report symptoms of depression, especially if they had a family history of the disorder.

Swartz said the new study examined a range of socioeconomic status and did not focus specifically on families affected by extreme poverty or neglect. She said the findings suggest that even modestly lower socioeconomic status is associated with biological differences that elevate adolescents' risk for depression.

Most of the team's work so far has focused on epigenetic chemical tags near the SLC6A4 gene because it helps control the brain's levels of serotonin, a neurochemical involved in clinical depression and other mood disorders. The more marks present just upstream of this gene, the less likely it is to be active.

In 2014, Williamson and Hariri first showed that the presence of marks near the SLC6A4 gene can predict the way a person's amygdala responds to threat. That study included both Williamson's TAOS and Hariri's DNS participants, but had looked at the chemical tags at a single point in time.

Looking at the changes in these markers over an extended time is a more powerful way to understand an individual's risk for depression, said Hariri, who is also a member of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences.

The team is now searching the genome for new markers that would predict depression. Ultimately, a panel of markers used in combination will lead to more accurate predictions, Swartz said.

They also hope to expand the age ranges of the study to include younger individuals and to continue following the TAOS participants into young adulthood.

"As they enter into young adulthood they are going to be experiencing more problems with depression or anxiety—or maybe substance abuse," Hariri said. "The extent to which our measures of their genomes and brains earlier in their lives continue to predict their relative health is something that's very important to know and very exciting for us to study."

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS