Blog

- Walking In Nature Leads To Measurable Brain Changes

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- September 25, 2016

-

Getty Images People often find a walk in nature to be a relaxing way of letting go of their stressful thoughts. However, do these walks have a measurable effect on the brain? Researchers at Stanford University examined the relationship between walking in nature and activity in the subgenual prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain related to ruminating thoughts. The study was discussed in an article of The New York Times:

Most of us today live in cities and spend far less time outside in green, natural spaces than people did several generations ago.

City dwellers also have a higher risk for anxiety, depression and other mental illnesses than people living outside urban centers, studies show.

These developments seem to be linked to some extent, according to a growing body of research. Various studies have found that urban dwellers with little access to green spaces have a higher incidence of psychological problems than people living near parks and that city dwellers who visit natural environments have lower levels of stress hormones immediately afterward than people who have not recently been outside.

But just how a visit to a park or other green space might alter mood has been unclear. Does experiencing nature actually change our brains in some way that affects our emotional health?

That possibility intrigued Gregory Bratman, a graduate student at the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources at Stanford University, who has been studying the psychological effects of urban living. In an earlier study published last month, he and his colleagues found that volunteers who walked briefly through a lush, green portion of the Stanford campus were more attentive and happier afterward than volunteers who strolled for the same amount of time near heavy traffic.

But that study did not examine the neurological mechanisms that might underlie the effects of being outside in nature.

So for the new study, which was published last week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Mr. Bratman and his collaborators decided to closely scrutinize what effect a walk might have on a person’s tendency to brood.

Brooding, which is known among cognitive scientists as morbid rumination, is a mental state familiar to most of us, in which we can’t seem to stop chewing over the ways in which things are wrong with ourselves and our lives. This broken-record fretting is not healthy or helpful. It can be a precursor to depression and is disproportionately common among city dwellers compared with people living outside urban areas, studies show.

Perhaps most interesting for the purposes of Mr. Bratman and his colleagues, however, such rumination also is strongly associated with increased activity in a portion of the brain known as the subgenual prefrontal cortex.

If the researchers could track activity in that part of the brain before and after people visited nature, Mr. Bratman realized, they would have a better idea about whether and to what extent nature changes people’s minds.

Mr. Bratman and his colleagues first gathered 38 healthy, adult city dwellers and asked them to complete a questionnaire to determine their normal level of morbid rumination.

The researchers also checked for brain activity in each volunteer’s subgenual prefrontal cortex, using scans that track blood flow through the brain. Greater blood flow to parts of the brain usually signals more activity in those areas.

Then the scientists randomly assigned half of the volunteers to walk for 90 minutes through a leafy, quiet, parklike portion of the Stanford campus or next to a loud, hectic, multi-lane highway in Palo Alto. The volunteers were not allowed to have companions or listen to music. They were allowed to walk at their own pace.

Immediately after completing their walks, the volunteers returned to the lab and repeated both the questionnaire and the brain scan.

As might have been expected, walking along the highway had not soothed people’s minds. Blood flow to their subgenual prefrontal cortex was still high and their broodiness scores were unchanged.

But the volunteers who had strolled along the quiet, tree-lined paths showed slight but meaningful improvements in their mental health, according to their scores on the questionnaire. They were not dwelling on the negative aspects of their lives as much as they had been before the walk.

They also had less blood flow to the subgenual prefrontal cortex. That portion of their brains were quieter.

These results “strongly suggest that getting out into natural environments” could be an easy and almost immediate way to improve moods for city dwellers, Mr. Bratman said.

But of course many questions remain, he said, including how much time in nature is sufficient or ideal for our mental health, as well as what aspects of the natural world are most soothing. Is it the greenery, quiet, sunniness, loamy smells, all of those, or something else that lifts our moods? Do we need to be walking or otherwise physically active outside to gain the fullest psychological benefits? Should we be alone or could companionship amplify mood enhancements?

“There’s a tremendous amount of study that still needs to be done,” Mr. Bratman said.

But in the meantime, he pointed out, there is little downside to strolling through the nearest park, and some chance that you might beneficially muffle, at least for awhile, your subgenual prefrontal cortex.

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- Neurofeedback Training of Amygdala Increases Emotional Regulation

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- September 18, 2016

-

Getty Images The amygdala plays a key role in emotional regulation. Researchers from Tel-Aviv University examined the impact of neurofeedback aimed at reducing EEG activity in the amygdala on emotional regulation in healthy participants. The study was discussed in a recent article in NeuroScientistNews:

Training the brain to treat itself is a promising therapy for traumatic stress. The training uses an auditory or visual signal that corresponds to the activity of a particular brain region, called neurofeedback, which can guide people to regulate their own brain activity.

However, treating stress-related disorders requires accessing the brain's emotional hub, the amygdala, which is located deep in the brain and difficult to reach with typical neurofeedback methods. This type of activity has typically only been measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which is costly and poorly accessible, limiting its clinical use.

A study published in Biological Psychiatry tested a new imaging method that provided reliable neurofeedback on the level of amygdala activity using electroencephalography (EEG), and allowed people to alter their own emotional responses through self-regulation of its activity.

"The major advancement of this new tool is the ability to use a low-cost and accessible imaging method such as EEG to depict deeply located brain activity," said both senior author Dr. Talma Hendler of Tel-Aviv University in Israel and The Sagol Brain Center at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, and first author Jackob Keynan, a PhD student in Hendler's laboratory, in an email toBiological Psychiatry.

The researchers built upon a new imaging tool they had developed in a previous study that uses EEG to measure changes in amygdala activity, indicated by its "electrical fingerprint". With the new tool, 42 participants were trained to reduce an auditory feedback corresponding to their amygdala activity using any mental strategies they found effective.

During this neurofeedback task, the participants learned to modulate their own amygdala electrical activity. This also led to improved downregulation of blood-oxygen level dependent signals of the amygdala, an indicator of regional activation measured with fMRI.

In another experiment with 40 participants, the researchers showed that learning to downregulate amygdala activity could actually improve behavioral emotion regulation. They showed this using a behavioral task invoking emotional processing in the amygdala. The findings show that with this new imaging tool, people can modify both the neural processes and behavioral manifestations of their emotions.

"We have long known that there might be ways to tune down the amygdala through biofeedback, meditation, or even the effects of placebos," said John Krystal, Editor of Biological Psychiatry. "It is an exciting idea that perhaps direct feedback on the level of activity of the amygdala can be used to help people gain control of their emotional responses."

The participants in the study were healthy, so the tool still needs to be tested in the context of real-life trauma. However, according to the authors, this new method has huge clinical implications.

The approach "holds the promise of reaching anyone anywhere," said Hendler and Keynan. The mobility and low cost of EEG contribute to its potential for a home-stationed bedside treatment for recent trauma patients or for stress resilience training for people prone to trauma.

Read the original article Here.

- Comments (2)

- Ultrasound Used to "Jumpstart" Patient's Brain

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- September 9, 2016

-

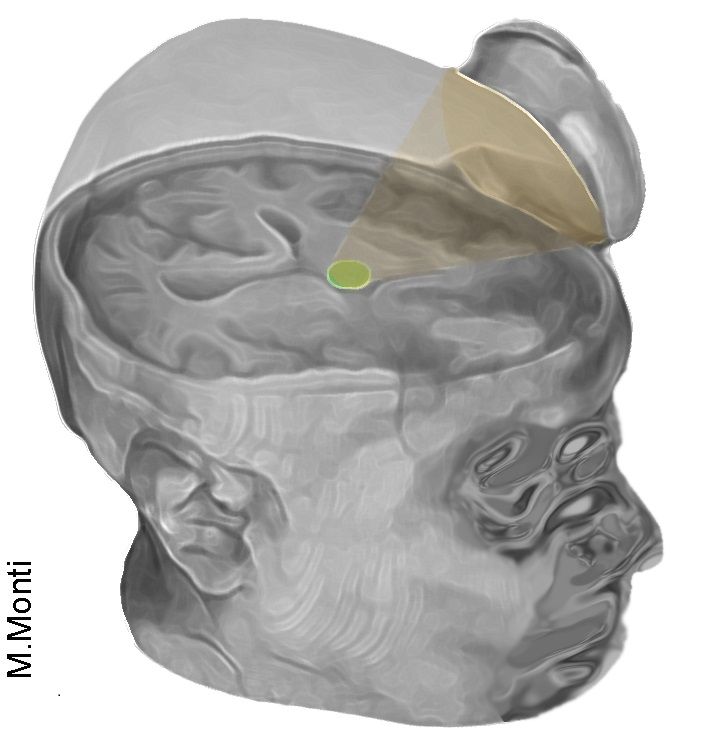

Photo Credit: Martin Monti/UCLA Researchers at UCLA used examined the use of ultrasound to stimulate the brain of a 25-year-old man in a coma. The treatment involved directing low-intensity acoustic energy to the patient’s thalamus, which is significantly underactivated in coma patients. The study was discussed in a recent article in Medical Xpress:

The technique uses sonic stimulation to excite the neurons in the thalamus, an egg-shaped structure that serves as the brain's central hub for processing information.

"It's almost as if we were jump-starting the neurons back into function," said Martin Monti, the study's lead author and a UCLA associate professor of psychology and neurosurgery. "Until now, the only way to achieve this was a risky surgical procedure known as deep brain stimulation, in which electrodes are implanted directly inside the thalamus," he said. "Our approach directly targets the thalamus but is noninvasive."

Monti said the researchers expected the positive result, but he cautioned that the procedure requires further study on additional patients before they determine whether it could be used consistently to help other people recovering from comas.

"It is possible that we were just very lucky and happened to have stimulated the patient just as he was spontaneously recovering," Monti said.

A report on the treatment is published in the journal Brain Stimulation. This is the first time the approach has been used to treat severe brain injury.

The technique, called low-intensity focused ultrasound pulsation, was pioneered by Alexander Bystritsky, a UCLA professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences in the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior and a co-author of the study. Bystritsky is also a founder of Brainsonix, a Sherman Oaks, California-based company that provided the device the researchers used in the study.

That device, about the size of a coffee cup saucer, creates a small sphere of acoustic energy that can be aimed at different regions of the brain to excite brain tissue. For the new study, researchers placed it by the side of the man's head and activated it 10 times for 30 seconds each, in a 10-minute period.

Monti said the device is safe because it emits only a small amount of energy—less than a conventional Doppler ultrasound.

Before the procedure began, the man showed only minimal signs of being conscious and of understanding speech—for example, he could perform small, limited movements when asked. By the day after the treatment, his responses had improved measurably. Three days later, the patient had regained full consciousness and full language comprehension, and he could reliably communicate by nodding his head "yes" or shaking his head "no." He even made a fist-bump gesture to say goodbye to one of his doctors.

"The changes were remarkable," Monti said.The technique targets the thalamus because, in people whose mental function is deeply impaired after a coma, thalamus performance is typically diminished. And medications that are commonly prescribed to people who are coming out of a coma target the thalamus only indirectly.

Under the direction of Paul Vespa, a UCLA professor of neurology and neurosurgery at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, the researchers plan to test the procedure on several more people beginning this fall at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. Those tests will be conducted in partnership with the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center and funded in part by the Dana Foundation and the Tiny Blue Dot Foundation.

If the technology helps other people recovering from coma, Monti said, it could eventually be used to build a portable device—perhaps incorporated into a helmet—as a low-cost way to help "wake up" patients, perhaps even those who are in a vegetative or minimally conscious state. Currently, there is almost no effective treatment for such patients, he said.

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS