Blog

- Being Only Child Affects Brain Structure And Personality

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- May 30, 2017

-

Getty Images It has long been hypothesized that individuals raised as only children develop a certain type of personality. However, does being an only child influence the structural development of an individual’s brain? Researchers at Southwest University in China investigated the relationship between the MRI scans and personalities of 303 college-aged participants. Findings indicated that only children were more likely to demonstrate greater flexibility in thinking and more grey matter volume in the supramarginal gyrus, which is associated with language perception and processing. The study was discussed in a recent article in Science Alert:

The mix of young people in China offers a broad pool of candidates for this area of research, owing to the nation's long-lasting one-child policy, which limited many but not all families to only raising a single child in between 1979 and 2015.

The common stereotype about being an only child is that growing up without siblings influences an individual's behaviour and personality traits, making them more selfish and less likely to share with their peers.

Previous research has borne some of this conventional wisdom out - but also demonstrated that only children can receive cognitive benefits as a result of their solo upbringing.

The participants in this latest study were approximately half only children (and half children with siblings), and were given cognitive tests designed to measure their intelligence, creativity, and personality, in addition to scanning their brains with MRI machines.

Although the results didn't demonstrate any difference in terms of intelligence between the two groups, they did reveal that only children exhibited greater flexibility in their thinking - a key marker of creativity per the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking.

While only children showed greater flexibility, they also demonstrated less agreeableness in personality tests under what's called the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Agreeableness is one of the five chief measures tested under the system, with the other four being extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience.

But more importantly than the behavioural data - which have been the focus of many other studies - the MRI results actually demonstrated neurological differences in the participants' grey matter volume (GMV) as a result of their upbringing.

In particular, the results showed that only children showed greater supramarginal gyrusvolumes - a portion of the parietal lobe thought to be associated with language perception and processing, and which in the study correlated to the only children's greater flexibility.

By contrast, the brains of only children revealed less volume in other areas, including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) - associated with emotional regulation, such as personality and social behaviours - which the team found to be correlated with their lower scores on agreeableness.

While the researchers aren't drawing firm conclusions on why only children exhibit these differences, they suggest it's possible that parents may foster greater creativity in only children by devoting more time to them - and possibly placing greater expectations on them.

Meanwhile, they hypothesise that only children's lesser agreeableness could result from excessive attention from family members, less exposure to external social groups, and more focus on solitary activities while growing up.

It's important to note that there are some limitations to the study - first off, all the participants were highly educated young people taken from a specific part of the world, and the results only reflect testing from one point in time.

That said, the researchers say it's the first evidence that differences in the anatomical structures of the brain are linked to differing behaviour in terms of flexibility and agreeableness.

"Additionally, our results contribute to the understanding of the neuroanatomical basis of the differences in cognitive function and personality between only-children and non-only-children," the authors write in their study.

While there's still a lot we don't understand about what's going on here, it's clear that there's a link between our family environments and the way our brain structure develops, and it'll be fascinating to see where this direction of research takes us in the future.

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- Bipolar Disorder and the Brain

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- May 18, 2017

-

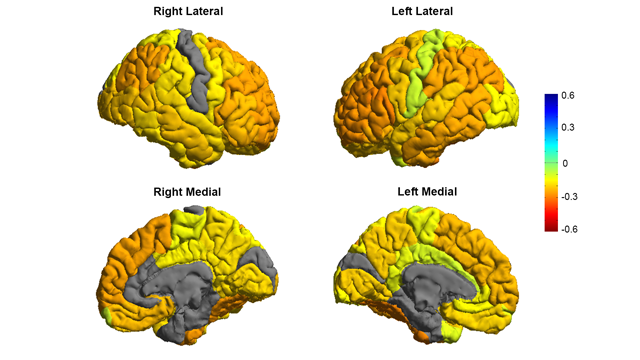

Image courtesy of the ENIGMA Bipolar Consortium/Derrek Hibar et al. Is the brain of someone with bipolar disorder different than the brain of their healthy counterpart? A study led by researchers from University of Southern California used MRI scans to compare the brains of individuals with bipolar disorder to the brains of individuals in a healthy control group. They found that the brains of people with bipolar disorder often had reductions in grey matter in frontal regions associated with self-control. The study was discussed in a recent article in Neuroscience for Technology Networks:

In the largest MRI study to date on patients with bipolar disorder, a global consortium published new research showing that people with the condition have differences in the brain regions that control inhibition and emotion.

By revealing clear and consistent alterations in key brain regions, the findings published in Molecular Psychiatry on May 2 offer insight to the underlying mechanisms of bipolar disorder.

"We created the first global map of bipolar disorder and how it affects the brain, resolving years of uncertainty on how people's brains differ when they have this severe illness," said Ole A. Andreassen, senior author of the study and a professor at the Norwegian Centre for Mental Disorders Research at the University of Oslo.

Bipolar disorder affects about 60 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. It is a debilitating psychiatric disorder with serious implications for those affected and their families. However, scientists have struggled to pinpoint neurobiological mechanisms of the disorder, partly due to the lack of sufficient brain scans.

The study was part of an international consortium led by the USC Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute at the Keck School of Medicine of USC: ENIGMA (Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta Analysis) spans 76 centers and includes 26 different research groups around the world.

Thousands of MRI scans

The researchers measured the MRI scans of 6,503 individuals, including 2,447 adults with bipolar disorder and 4,056 healthy controls. They also examined the effects of commonly used prescription medications, age of illness onset, history of psychosis, mood state, age and sex differences on cortical regions.

The study showed thinning of gray matter in the brains of patients with bipolar disorder when compared with healthy controls. The greatest deficits were found in parts of the brain that control inhibition and motivation - the frontal and temporal regions.

Some of the bipolar disorder patients with a history of psychosis showed greater deficits in the brain's gray matter. The findings also showed different brain signatures in patients who took lithium, anti-psychotics and anti-epileptic treatments. Lithium treatment was associated with less thinning of gray matter, which suggests a protective effect of this medication on the brain.

"These are important clues as to where to look in the brain for therapeutic effects of these drugs," said Derrek Hibar, first author of the paper and a professor at the USC Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute when the study was conducted. He was a former visiting researcher at the University of Oslo and is now a senior scientist at Janssen Research and Development, LLC.

Early detection

Future research will test how well different medications and treatments can shift or modify these brain measures as well as improve symptoms and clinical outcomes for patients.

Mapping the affected brain regions is also important for early detection and prevention, said Paul Thompson, director of the ENIGMA consortium and co-author of the study.

"This new map of the bipolar brain gives us a roadmap of where to look for treatment effects," said Thompson, an associate director of the USC Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute at the Keck School of Medicine. "By bringing together psychiatrists worldwide, we now have a new source of power to discover treatments that improve patients' lives."

This article has been republished from materials provided by University of Southern California. Note: material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source.Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS