Blog

- Amygdalar Activity Predicts Cardiovascular Events, Study Finds

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- January 31, 2017

-

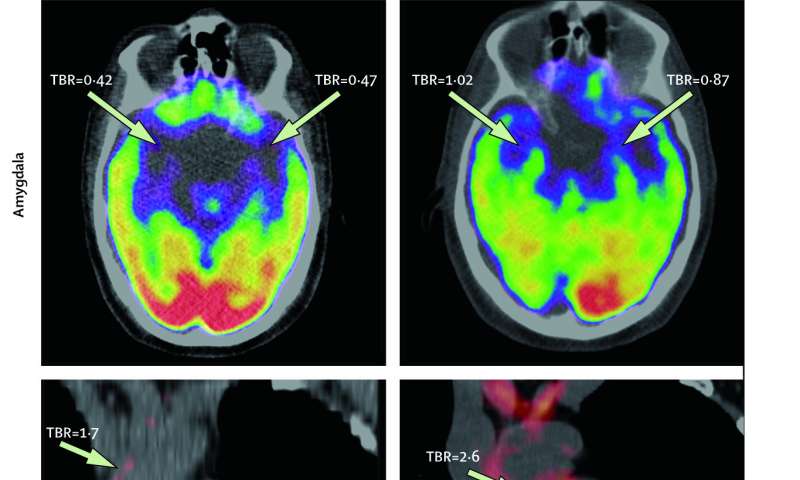

Tawakol et al, 2017, The Lancet It is well known that emotional stress is related to risk of cardiovascular disease. However, the mechanism of this phenomenon has not always been clearly understood. Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Tufts University collaborated to investigate the relationship between amygdalar activity and cardiovascular events. Findings indicated that amygdalar activity predicted bone-marrow activity and arterial inflammation. The study was discussed in a recent article in Medical Xpress:

"While the link between stress and heart disease has long been established, the mechanism mediating that risk has not been clearly understood," says Ahmed Tawakol, MD, co-director of the Cardiac MR PET CT Program in the MGH Division of Cardiology and lead author of the paper. "Animal studies have shown that stress activates bone marrow to produce white blood cells, leading to arterial inflammation, and this study suggests an analogous path exists in humans. Moreover, this study identifies, for the first time in animal models or humans, the region of the brain that links stress to the risk of heart attack and stroke."

The paper reports on two complementary studies. The first, conducted at MGH, analyzed imaging and medical records data from almost 300 individuals who had PET/CT brain imaging, primarily for cancer screening, using a radiopharmaceutical called FDG that both measures the activity of areas within the brain and also reflects inflammation within arteries. All participants in that study had no active cancer or cardiovascular disease at the time of imaging and each had information in their medical records on at least three additional clinical visits in the two to five years after imaging. The second study, conducted at the Translational and Molecular Imaging Institute (TMII) at ISMMS in New York, enrolled 13 individuals with a history of post-traumatic stress disorder, who were evaluated for their current levels of perceived stress and received FDG-PET scanning to measure both amygdala activity and arterial inflammation.

Among participants in the larger, longitudinal study, 22 experienced a cardiovascular event—such as a heart attack, stroke or episodes of angina—in the follow-up period; and the prior level of activity in the amygdala strongly predicted the risk of a subsequent cardiovascular event. That association remained significant after controlling for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and after controlling for presence of symptom-free atherosclerosis at the time of imaging. The association became even stronger when the team used a more stringent definition of cardiovascular events—major adverse cardiovascular events.

Amygdalar activity was also associated with the timing of events, as those with the highest levels of activity had events sooner than those with less extreme elevation, and greater amygdalar activity was also linked to elevated activity of the blood-cell-forming tissue in the bone marrow and spleen and to increased arterial inflammation. In the smaller study, participants' current stress levels were strongly associated with both amygdalar activity and arterial inflammation.

Co-senior author Zahi A. Fayad, PhD, vice-chair for Research in the Department of Radiology and the director of TMII at ISMMS in New York, says, "This pioneering study provides more evidence of a heart-brain connection, by elucidating a link between resting metabolic activity in the amygdala, a marker of stress, and subsequent cardiovascular events independently of established cardiovascular risk factors. We also show that amygdalar activity is related to increased associated perceived stress and to an increased vascular inflammation and hematopoeitic activity."

Tawakol adds, "These findings suggest several potential opportunities to reduce cardiovascular risk attributable to stress. It would be reasonable to advise individuals with increased risk of cardiovascular disease to consider employing stress-reduction approaches if they feel subjected to a high degree of psychosocial stress. However, large trials are still needed to confirm that stress reduction improves cardiovascular disease risk. Further, pharmacological manipulation of the amygdalar-bone marrow-arterial axis may provide new opportunities to reduce cardiovascular disease. In addition, increased stress associates with other diseases, such as cancer and inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. So it will be important to evaluate whether calming this stress mechanism produces benefits in those diseases as well."

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- Weaker Connectivity In Brains of Those with Bipolar Disoder

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- January 29, 2017

-

Getty Images According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 2.6 percent of the U.S. adult population suffers from bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is a debilitating illness that can involve several years of mental health treatment before a proper diagnosis is given. Australian researchers recently conducted a study investigating the use of MRI scans of the brain in detecting biomarkers for the disorder. Findings indicated that participants suffering from bipolar disorder had weaker connectivity in emotional centers of the brain, such as right-sided fronto-temporal and temporal areas, than their healthy counterparts. The study was discussed in a recent article in MedicalXpress:

It is hoped the findings will lead to new tools to identify and manage those at risk before the onset of the disorder and help reduce its impact once it develops.

The study, published today in the prestigious Nature journal Molecular Psychiatry, was a collaboration between researchers from QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane and UNSW in Sydney.

Researchers conducted MRI scans on the brains of three groups: people who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder; people who had a first-degree relative (parent, sibling or child) with bipolar and who were at high genetic risk themselves; and people unaffected by bipolar disorder.

They found networks of weaker connections between different brain regions in both the bipolar and high-risk subjects and disturbances in the connections responsible for regulating emotional and cognitive processes.

"We know that changes in these brain wiring patterns will impact upon a person's capacity to perform key emotional and cognitive functions," said study author Scientia Professor Philip Mitchell from UNSW's School of Psychiatry.

"Each year we will be following up with participants from this study who are at high genetic risk of developing bipolar disorder, to see if the brain changes identified in MRI scans reveal who will develop episodes of mania," Professor Mitchell said.

Bipolar disorder is a debilitating illness affecting about one in 70 Australians. It typically involves unstable mood swings between manic 'highs' and depressive 'lows'. The age of onset is usually between 18 and 30 years.

Professor Michael Breakspear, from QIMR Berghofer and Brisbane's Metro North Hospital and Health Service, said the research team hoped to use the findings to develop a way of identifying those at risk of bipolar before the onset of the disorder.

"At the moment we don't have any markers or tests for predicting who is at risk of developing bipolar disorder, as we do for heart disease," Professor Breakspear said.

"If we can develop a tool to identify and confirm those who are at the very highest risk, then we can advise them on how to minimise their risk of developing bipolar, for example, by avoiding illicit drugs and minimising stress. These discoveries may open the door to starting people on medication before the illness, to reduce the risk of manic episodes before the first one occurs.

"Our long-term goal is to develop imaging-based diagnostic tests for bipolar. At the moment, diagnosis relies on the opinion of a doctor. Recent UNSW-led research found an average delay of six years between when a person with bipolar experiences their first manic episode and when they receive a correct diagnosis," Professor Breakspear said.

"Many people are incorrectly diagnosed with depression or other disorders. This delays the start of proper treatment with medications that are specific to bipolar disorder. Bipolar has the highest suicide rate of any mental illness, so it's crucial that we diagnose people correctly straight away so they can start receiving the right treatment."

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Landsdowne Foundation.

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- Underactivated Reward Center Related to Musical Anhedonia

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- January 22, 2017

-

Getty Images Musical anhedonia, a condition in which individuals are unable to enjoy music, affects as much as 5% of the population. Researchers at the University of Barcelona compared the brain scans of people suffering from musical anhedonia to those of their healthy counterparts. The researchers found that those suffering from the condition showed underactivity in the nucleus accumbens, a reward center in the brain. The study was discussed in a recent article in the Worthing Herald:

Researchers found people that get little pleasure from music, who are known as musical anhedonics, show less activity in the ‘reward centre’ of the brain when songs are playing.

But musical anhedonics are able to respond to other enjoyable activities like gambling, which suggests there could be a missing link between their reward centre and the brain region which controls processing sounds.

The condition is believed to affect up to five per cent of the population.

Psychology PhD student Noelia Martínez-Molina, who led the study, said: “Although music is ubiquitous in human societies, there are some people for whom music holds no reward value despite normal perceptual ability and preserved reward-related responses in other domains.”

As part of the study at the University of Barcelona, Spain, researchers recruited 45 healthy people who completed a questionnaire measuring their level of sensitivity to music and then divided them into three groups based on their responses.

The participants were then asked to listen to music while lying inside an MRI scanner.

Scientists used the scanner to measure activity in the reward centre of the participants’ brains.They found that people who said they didn’t enjoy music showed a reduction in the activity of the nucleus accumbens, a key region in the reward centre of the brain, when songs were playing.

In contrast, people who said they liked music showed enhanced activity in the reward centre.

Researchers also analysed the brains of the music anhedonics while they were gambling to check if their reward centres could respond to other pleasurable activities.

Dr Martínez-Molina said: “We demonstrate that the music anhedonic participants showed selective reduction of activity for music in the nucleus accumbens, but normal activation levels for a monetary gambling task.”

The researchers said the fact musical anhedonics are able to respond to enjoyable activities other than music suggests there could be a missing link between the areas in their brains that control sound and pleasure.

Previous studies have shown that children on the autistic spectrum, who do not find the human voice to be pleasurable, experience a similar disconnection between the brain regions that control sound processing and pleasure.

Dr Robert Zatorre, a researcher from Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Canada, who co-authored the study, said: “These findings not only help us to understand individual variability in the way the reward system functions, but also can be applied to the development of therapies for treatment of reward-related disorders, including apathy, depression, and addiction.”

The study was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- fMRI Neurofeedback Used to Increase Confidence and Decrease Fear

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- December 31, 2016

-

What does confidence look like in the brain? Is it possible to directly train confidence? Researchers at UCLA investigated the use of fMRI neurofeedback to increase confidence and decrease fear. Researchers decoded intricate patterns of brain activity associated with confidence and fear. Neurofeedback was then used to reward the brain activity patterns, which were unconscious to the participants. The study was discussed in a recent article in MedicalXpress:

The approach, developed by a UCLA-led team of neuroscientists, is described in two new papers, published in the journals Nature Communications and Nature Human Behaviour.

Their method could have implications for treating people with depression, dementia and anxiety disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, said Hakwan Lau, a UCLA associate professor of psychology and the senior author of both studies. It could also play a role in improving leadership training for executives and managers.

In the Nature Human Behaviour study, the researchers showed that they could reduce the brain's manifestation of fear using a procedure called decoded neurofeedback, which involves identifying complex patterns of brain activity linked to a specific memory, and then giving feedback to the subject—for example, in the form of a reward—based on their brain activity.

The researchers tested the technique on 17 undergraduate and graduate students in Japan. Participants were seated in a functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, scanner and shown patterns of vertical lines in four colors—red, green, blue and yellow. The blue and yellow images were always shown without shocks, but the red and green patterns were often accompanied by a small electrical shock administered to their feet.

As a result, the subjects' brain patterns began to register fear for the red and green images. But the scientists learned that they could use decoded neurofeedback to lessen the subjects' fear of the red pattern. They did this by giving the subjects a small cash reward—the equivalent of about 10 cents—each time they spontaneously thought about the red lines (but gave no rewards for thinking about the green lines), which the scientists could determine in real time based on their brain activity.

The following day, researchers tested whether the participants still had a fear response to the vertical lines. The red pattern, which had been frightening because it was paired with shocks, became less so because it now was paired with a positive outcome. With the reward as part of the equation, researchers found that participants perspired much less than when they had seen the red lines previously, and their brain's fear signal, centered in the amygdala, was significantly reduced.

"After just three days of training, we saw a significant reduction of fear," Lau said. "We changed the association of the 'fear object' from negative to positive."

Participants were not told what they had to do to earn the money—only that the reward was based on their brain activity and that they should try to earn as much money as possible. And each time participants were told they had won money, their brains demonstrated more of the same pattern that had just won them the cash reward.

Although participants tried to guess which of their thoughts were triggering the rewards—some guessed humming music or thinking about a girlfriend, for example—none actually figured out how they earned the money or recognized that the researchers had effectively reduced their fear of the red lines.

"Their brain activity was completely unconscious," Lau said. "That makes sense; a lot of our brain activity is unconscious."

Participants did still register fear on their fMRI scans when they saw the green pattern because, without the financial rewards, they still primarily associated the color with shocks.

The findings could help improve upon standard behavioral therapy, in which a person who is afraid of a certain object is exposed to photos of that object, or even the object itself—which can be frightening enough that many people cannot complete treatment. Lau said using "unconscious fear reduction," like in the experiment, could be more effective in many cases.

Instilling confidence

In the Nature Communications study, which was published today, Lau and his colleagues used decoded neurofeedback to increase people's confidence levels.

Ten participants were seated in an fMRI scanner and asked to watch a computer screen with hundreds of dots moving in different directions.

Participants were asked whether the majority of dots were moving to the left or the right, and how confident they were in their responses. That initial feedback gave the researchers a chance to see how high confidence and low confidence were represented in brain patterns.

Participants then were shown dots moving in random motion and told to think about anything—and that certain thoughts would earn them cash rewards. Every time the brain pattern looked like it was representing high confidence, the participant received a reward of up to the equivalent of 10 cents; subjects received smaller rewards if their brain activity indicated less confidence.

Next, the researchers showed the students the images from the first phase of the experiment—with numerous dots primarily moving in one direction or the other. The scientists found that although students weren't any better at guessing the primary direction of the dots' motion, they had become more confident in their guesses.

By studying brain patterns, Lau said, neuroscientists can decode people's thoughts about food, love, money and many other concepts, which eventually could help them design treatments for eating disorders, gambling addiction and more. The researchers next will determine whether the techniques described in the papers can be used to help patients with real phobias.

"We are cautiously optimistic," he said.

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Reactivates Lost Memory

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- December 19, 2016

-

Photo Credit: Getty Images One’s ability to hold information in working memory is essential to daily functioning. Without working memory one would not be able to dial a phone number before forgetting it or remember the location of a chair in a room in order to avoid bumping into it. Previously, researchers believed that the brain needed to sustain elevated activity to maintain the memory, and once the activity ceased the memory was lost. However, researchers at University of Wisconsin Madison found that transcranial magnetic stimulation can retrieve memories once elevated brain activity has ceased. The study was discussed in a recent article in NeuroScientist News:

"A lot of mental illness is associated with the inability to choose what to think about," says Brad Postle, a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin- (UW-) Madison. "What we're taking are first steps toward looking at the mechanisms that give us control over what we think about."

Postle's lab is challenging the idea that working memory remembers things through sustained brain activity. They caught brains tucking less-important information away somewhere beyond the reach of the tools that typically monitor brain activity—and then they snapped that information back into active attention with magnets.

Their latest study is published in the journal Science.

According to Postle, it's important to note that most people feel they are able to concentrate on a lot more than their working memory can actually hold. It's a bit like vision, in which it feels like we're seeing everything in our field of view, but details slip away unless you re-focus on them regularly.

"The notion that you're aware of everything all the time is a sort of illusion your consciousness creates," says Postle. "That is true for thinking, too. You have the impression that you're thinking of a lot of things at once, holding them all in your mind. But lots of research shows us you're probably only actually attending to—are conscious of in any given moment—just a very small number of things."

Postle's group conducted a series of experiments in which people were asked to remember two items representing different types of information (they used words, faces and directions of motion) because they'd be tested on their memories.

When the researchers gave their subjects a cue as to the type of question coming—a face, for example, instead of a word—the electrical activity and blood flow in the brain associated with the word memory disappeared. But if a second cue came letting the subject know they would now be asked about that word, the brain activity would jump back up to a level indicating it was the focus of attention.

"People have always thought neurons would have to keep firing to hold something in memory. Most models of the brain assume that," says Postle. "But we're watching people remember things almost perfectly without showing any of the activity that would come with a neuron firing. The fact that you're able to bring it back at all in this example proves it's not gone. It's just that we can't see evidence for its active retention in the brain."

The researchers were also able to bring the seemingly abandoned items back to mind without cueing their subjects. Using a technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to apply a focused electromagnetic field to a precise part of the brain involved in storing the word, they could trigger the sort of brain activity representative of focused attention.

Furthermore, if they cued their research subjects to focus on a face (causing brain activity associated with the word to drop off), a well-timed pulse of transcranial magnetic stimulation would snap the stowed memory back into attention, and prompt the subjects to incorrectly think that they had been cued to focus on the word.

"We think that memory is there, but not active," says Postle, whose work is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health. "More than just showing us it's there, the TMS can actually make that memory temporarily active again."

The study—conducted by Postle with Nathan Rose, a former UW-Madison postdoctoral researcher who is now a professor of psychology at the University of Notre Dame, and UW-Madison graduate students in psychology and neuroscience—suggests a state of memory apart from the spotlight attention of active working memory and the deep storage of more significant things in long-term memory.

"What's still unknown here is how the brain determines what falls away, and what enables you to retrieve things in the short-term if you need them," Postle says.

Studying how the brain apportions attention could eventually influence the way we understand and treat mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, in which patients focus on hallucinations instead of reality, and depression, which seems strongly related to spending an unhealthy amount of time dwelling on negative things.

"We are making some interesting progress with very basic research," says Postle. "But you can picture a point at which this work could help people control their attention, choose what they think about, and manage or overcome some very serious problems associated with a lack of control."

Read the original article here

- Comments (0)

- Spiritual Experience Studied Using fMRI

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- December 9, 2016

-

Photo Credit: University of Utah Health Sciences Researchers from University of Utah as well as Harvard University investigated the brain’s response to a spiritual experience. The study utilized fMRI scans to measure the response of Mormon participants’ brains while viewing Mormon quotations and video of religious content. Participants reported experiencing feelings of peace and physical warmth. Findings indicated that areas of the brain related to focused attention, processing rewards, and moral reasoning. The study was discussed in a recent article in Medical Xpress:

Religious and spiritual experiences activate the brain reward circuits in much the same way as love, sex, gambling, drugs and music, report researchers at the University of Utah School of Medicine. The findings will be published Nov. 29 in the journal Social Neuroscience.

"We're just beginning to understand how the brain participates in experiences that believers interpret as spiritual, divine or transcendent," says senior author and neuroradiologist Jeff Anderson, M.D., Ph.D. "In the last few years, brain imaging technologies have matured in ways that are letting us approach questions that have been around for millennia."

Specifically, the investigators set out to determine which brain networks are involved in representing spiritual feelings in one group, devout Mormons, by creating an environment that triggered participants to "feel the Spirit." Identifying this feeling of peace and closeness with God in oneself and others is a critically important part of Mormons' lives—they make decisions based on these feelings; treat them as confirmation of doctrinal principles; and view them as a primary means of communication with the divine.

During fMRI scans, 19 young-adult church members—including seven females and 12 males—performed four tasks in response to content meant to evoke spiritual feelings. The hour-long exam included six minutes of rest; six minutes of audiovisual control (a video detailing their church's membership statistics); eight minutes of quotations by Mormon and world religious leaders; eight minutes of reading familiar passages from the Book of Mormon; 12 minutes of audiovisual stimuli (church-produced video of family and Biblical scenes, and other religiously evocative content); and another eight minutes of quotations.

During the initial quotations portion of the exam, participants—each a former full-time missionary—were shown a series of quotes, each followed by the question "Are you feeling the spirit?" Participants responded with answers ranging from "not feeling" to "very strongly feeling."

Researchers collected detailed assessments of the feelings of participants, who, almost universally, reported experiencing the kinds of feelings typical of an intense worship service. They described feelings of peace and physical sensations of warmth. Many were in tears by the end of the scan. In one experiment, participants pushed a button when they felt a peak spiritual feeling while watching church-produced stimuli.

"When our study participants were instructed to think about a savior, about being with their families for eternity, about their heavenly rewards, their brains and bodies physically responded," says lead author Michael Ferguson, Ph.D., who carried out the study as a bioengineering graduate student at the University of Utah.

Based on fMRI scans, the researchers found that powerful spiritual feelings were reproducibly associated with activation in the nucleus accumbens, a critical brain region for processing reward. Peak activity occurred about 1-3 seconds before participants pushed the button and was replicated in each of the four tasks. As participants were experiencing peak feelings, their hearts beat faster and their breathing deepened.

In addition to the brain's reward circuits, the researchers found that spiritual feelings were associated with the medial prefrontal cortex, which is a complex brain region that is activated by tasks involving valuation, judgment and moral reasoning. Spiritual feelings also activated brain regions associated with focused attention.

"Religious experience is perhaps the most influential part of how people make decisions that affect all of us, for good and for ill. Understanding what happens in the brain to contribute to those decisions is really important," says Anderson, noting that we don't yet know if believers of other religions would respond the same way. Work by others suggests that the brain responds quite differently to meditative and contemplative practices characteristic of some eastern religions, but so far little is known about the neuroscience of western spiritual practices.

The study is the first initiative of the Religious Brain Project, launched by a group of University of Utah researchers in 2014, which aims to understand how the brain operates in people with deep spiritual and religious beliefs.

Read the original article Here

- Comments (0)

- The Impact of Exercise on the Brain

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- November 26, 2016

-

Most students of psychology have learned of the study by Marian Diamond in which a group of rats living in an enriched environment had a thicker, more developed cortex than rats living in an impoverished environment. If the brains of rats can be changed, a questions is raised: What can change the brains of humans? Former student of Diamond, neuroscientist Wendy Suzuki has devoted her career to the effect of physical exercise on the human brain. Suzuki’s life and research was discussed in a recent article in The Huffington Post:

Devoted to solving intricate physiological questions about the brain for almost her entire adult life, Wendy Suzuki, a neuroscientist at New York University, was proud of her work. But the long hours dedicated to research eventually left her feeling socially isolated and physically weak.

Taking up a habit of regularly visiting the gym changed all that — so profoundly that she decided to also change the focus of her studies and become a beginner researcher in the neuroscience of exercise at 51 years old. That meant giving up the reputation she had built over 25 years to enter a field where no one knew her.

“It was a hard decision and it was scary,” Suzuki said. “But once I made the decision I knew it was the right one.”

She also thought it was a particularly good decision because the results of her work, which focuses on understanding the effects of exercise on the brain, could quickly lead to tangible benefits.

“The thing that was really exciting and appealing is that this was the kind of research that could immediately be applied to helping people live their life better,” she said.

We’ve long known that exercise makes for a healthier, fitter body. But its similar effects on the brain have only come to light in recent years. In fact, just the idea that the brain can change at all in response to experiences is something that had not garnered much evidence until the late 20th century. One of the first experiments to show the flexibility of the brain was done in 1972, when researchers put mice in a fun cage equipped with running wheels and toys, and found the cortex area of the rodents’ brains grew thicker, whereas it didn’t in mice kept in a dull, small cage.

Later it was found that although we are endowed with a set amount of long-lasting neurons, new neurons could still be born in adulthood. More importantly, this occurs in the hippocampus, a critical structure for memory and learning. And what can boost the generation of new neurons there? Aerobic exercise.

The hippocampus is one of the primary targets of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. So building up the hippocampus over a lifetime could potentially delay the effects of diseases.

“Exercise is not going to cure Alzheimer’s or dementia but it anatomically strengthens two of the key targets of both those diseases, the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex,” Suzuki said. “Your hippocampus will be bigger if you exercise regularly, so that means that it’s going to take that much longer for the plaques and tangles of Alzheimer’s disease to cause behavioral effects. That means months, or hopefully years, of higher cognitive function.”

The creation of new neurons, or neurogenesis, doesn’t happen overnight, however. Neurons don’t just pop up fully formed and fully integrated. They are born as immature cells and take several months to grow.

But that’s not to say that all positive effects will be delayed by three or four months if you start exercising now. As many people have noticed firsthand, exercising also makes the mind sharper and attention more focused. That’s because another brain area heavily affected by aerobic exercise is the prefrontal cortex, an area in charge of high-level cognition, executive functions, decision-making and attention.

Exactly how it happens is not fully known, but it seems that the prefrontal cortex is actually relaxing during intense physical activity. It then gets a rebound increase in blood flow after the exercise, enabling it to work at full speed. It’s also possible that the same bodily changes that help new neurons grow in the hippocampus are also at work in the prefrontal cortex and help grow glial cells and blood vessels.

So which type of exercise is best from the brain’s point of view? Here’s what we can tell from research so far:

Mood: Walking, aerobic exercise and high-intensity interval training can improve your mood.

“We recently did a study comparing the three. All three of them improved mood but the one that did the most was walking. That’s good news for people who don’t have a high-level aerobic regime on hand,” Suzuki said.

Memory: The best evidence for hippocampal neurogenesis is continuous aerobic exercise.

“You have to get your heart rate up. So a good 45-minute workout,” Suzuki said.

Attention: Aerobic exercise is again the best option if you want to boost attention. But unlike with memory, the improvements are more acute and come faster. Jogging, biking and treadmill running are all good options for getting a boost in the prefrontal cortex.

Read the orginal article Here

- Comments (0)

- Trauma Impacts Brains of Boys and Girls Differently

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- November 19, 2016

-

A recent study from researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine found differences in the brain structures of boys and girls suffering from traumatic experiences. Interestingly, brains scans found no differences between the brains of boys and girls in the healthy control group. However, in the brains of those who experienced trauma there were significant differences in the volume and surface of the anterior circular sulcus. The study was discussed in a recent article in Medical Xpress:

Among youth with post-traumatic stress disorder, the study found structural differences between the sexes in one part of the insula, a brain region that detects cues from the body and processes emotions and empathy. The insula helps to integrate one's feelings, actions and several other brain functions.

The findings will be published online Nov. 11 in Depression and Anxiety. The study is the first to show differences between male and female PTSD patients in a part of the insula involved in emotion and empathy.

"The insula appears to play a key role in the development of PTSD," said the study's senior author, Victor Carrion, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford. "The difference we saw between the brains of boys and girls who have experienced psychological trauma is important because it may help explain differences in trauma symptoms between sexes."

Smaller insula in traumatized girls

Among young people who are exposed to traumatic stress, some develop PTSD while others do not. People with PTSD may experience flashbacks of traumatic events; may avoid places, people and things that remind them of the trauma; and may suffer a variety of other problems, including social withdrawal and difficulty sleeping or concentrating. Prior research has shown that girls who experienced trauma are more likely to develop PTSD than boys who experience trauma, but scientists have been unable to determine why.

The research team conducted MRI scans of the brains of 59 study participants ages 9-17. Thirty of them—14 girls and 16 boys—had trauma symptoms, and 29 others—the control group of 15 girls and 14 boys—did not. The traumatized and nontraumatized participants had similar ages and IQs. Of the traumatized participants, five had experienced one episode of trauma, while the remaining 25 had experienced two or more episodes or had been exposed to chronic trauma.

The researchers saw no differences in brain structure between boys and girls in the control group. However, among the traumatized boys and girls, they saw differences in a portion of the insula called the anterior circular sulcus. This brain region had larger volume and surface area in traumatized boys than in boys in the control group. In addition, the region's volume and surface area were smaller in girls with trauma than among girls in the control group.

Findings could help clinicians

"It is important that people who work with traumatized youth consider the sex differences," said Megan Klabunde, PhD, the study's lead author and an instructor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. "Our findings suggest it is possible that boys and girls could exhibit different trauma symptoms and that they might benefit from different approaches to treatment."

The insula normally changes during childhood and adolescence, with smaller insula volume typically seen as children and teenagers grow older. Thus, the findings imply that traumatic stress could contribute to accelerated cortical aging of the insula in girls who develop PTSD, Klabunde said.

"There are some studies suggesting that high levels of stress could contribute to early puberty in girls," she said.

The researchers also noted that their work may help scientists understand how experiencing trauma could play into differences between the sexes in regulating emotions. "By better understanding sex differences in a region of the brain involved in emotion processing, clinicians and scientists may be able to develop sex-specific trauma and emotion dysregulation treatments," the authors write in the study.

To better understand the findings, the researchers say what's needed next are longitudinal studies following traumatized young people of both sexes over time. They also say studies that further explore how PTSD might manifest itself differently in boys and girls, as well as tests of whether sex-specific treatments are beneficial, are needed.

The work is an example of Stanford Medicine's focus on precision health, the goal of which is to anticipate and prevent disease in the healthy and precisely diagnose and treat disease in the ill.

Read the original article here

- Comments (0)

- Brain Circuitry Related to Context Processing Involved in PTSD

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- October 31, 2016

-

Why are some individuals vulnerable to PTSD when others are not? Researchers at University of Michigan theorize that dysregulation in the brain’s circuity related to context processing, hippocampal-prefrontal-thalamic circuitry, is at the core of PTSD. The theory was discussed in a recent article in Medical Xpress:

All experts in the field now agree that PTSD indeed has its roots in very real, physical processes within the brain - and not in some sort of psychological "weakness". But no clear consensus has emerged about what exactly has gone "wrong" in the brain.

In a Perspective article published this week in Neuron, a pair of University of Michigan Medical School professors—who have studied PTSD from many angles for many years—put forth a theory of PTSD that draws from and integrates decades of prior research. They hope to stimulate interest in the theory and invite others in the field to test it.

The bottom line, they say, is that people with PTSD appear to suffer from disrupted context processing. That's a core brain function that allows people and animals to recognize that a particular stimulus may require different responses depending on the context in which it is encountered. It's what allows us to call upon the "right" emotional or physical response to the current encounter.

A simple example, they write, is recognizing that a mountain lion seen in the zoo does not require a fear or "flight" response, while the same lion unexpectedly encountered in the backyard probably does.

For someone with PTSD, a stimulus associated with the trauma they previously experienced - such as a loud noise or a particular smell—triggers a fear response even when the context is very safe. That's why they react even if the noise came from the front door being slammed, or the smell comes from dinner being accidentally burned on the stove.

Context processing involves a brain region called the hippocampus, and its connections to two other regions called the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala. Research has shown that activity in these brain areas is disrupted in PTSD patients. The U-M team thinks their theory can unify wide-ranging evidence by showing how a disruption in this circuit can interfere with context processing and can explain most of the symptoms and much of the biology of PTSD.

"We hope to put some order to all the information that's been gathered about PTSD from studies of human patients, and of animal models of the condition," says Israel Liberzon, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at U-M and a researcher at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System who also treats veterans with PTSD. "We hope to create a testable hypothesis, which isn't as common in mental health research as it should be. If this hypothesis proves true, maybe we can unravel some of the underlying pathophysiological processes, and offer better treatments."

Liberzon and his colleague, James Abelson, M.D., Ph.D., describe in their piece models of PTSD that have emerged in recent years, and lay out the evidence for each. The problem, they say, is that none of these models sufficiently explains the various symptoms seen in patients, nor all of the complex neurobiological changes seen in PTSD and in animal models of this disorder.

The first model, abnormal fear learning, is rooted in the amygdala - the brain's 'fight or flight' center that focuses on response to threats or safe environments. This model emerged from work on fear conditioning, fear extinction and fear generalization.

The second, exaggerated threat detection, is rooted in the brain regions that figure out what signals from the environment are "salient", or important to take note of and react to. This model focuses on vigilance and disproportionate responses to perceived threats.

The third, involving executive function and regulation of emotions, is mainly rooted in the prefrontal cortex - the brain's center for keeping emotions in check and planning or switching between tasks.

By focusing only on the evidence bolstering one of these theories, researchers may be "searching under the streetlight", says Liberzon. "But if we look at all of it in the light of context processing disruption, we can explain why different teams have seen different things. They're not mutually exclusive."

The main thing, says Liberzon, is that "context is not only information about your surroundings - it's pulling out the correct emotion and memories for the context you are in."

A deficit in context processing would lead PTSD patients to feel "unmoored" from the world around them, unable to shape their responses to fit their current contexts. Instead, their brains would impose an "internalized context"—one that always expects danger—on every situation.

This type of deficit, arising in the brain from a combination of genetics and life experiences, may create vulnerability to PTSD in the first place, they say. After trauma, this would generate symptoms of hypervigilance, sleeplessness, intrusive thoughts and dreams, and inappropriate emotional and physical outbursts.

Liberzon and Abelson think that testing the context processing theory will enhance understanding of PTSD, even if all of its details are not verified. They hope the PTSD community will help them pursue the needed research, in PTSD patients and in animal models. They put forth specific ideas in the Neuron paper to encourage that, and are embarking on such research themselves.

The U-M/VA team is currently recruiting people with PTSD - whether veterans or not - for studies involving brain imaging and other tests.

In the meantime, they note that there is a growing set of therapeutic tools that can help patients with PTSD, such as cognitive behavioral therapy mindfulness training and pharmacological approaches. These may work by helping to anchor PTSD patients in their current environment, and may prove more effective as researchers learn how to specifically strengthen context processing capacities in the brain.

Read the original article here

- Comments (0)

- EEG Can Be Used For Cyber Security

- By Jason von Stietz, M.A.

- October 29, 2016

-

Getty Images Finger print scans are widely used as a method of proving identification and can even be used to access a secured cyber system. However, finger print scans can be stolen or replicated. So, what is the next step in cyber security? Researchers are currently investigating how EEG can be used as a means of biometric authentication. The research was discussed in a recent article in Neuroscience News:

Cyber security and authentication have been under attack in recent months as, seemingly every other day, a new report of hackers gaining access to private or sensitive information comes to light. Just recently, more than 500 million passwords were stolen when Yahoo revealed its security was compromised.

Securing systems has gone beyond simply coming up with a clever password that could prevent nefarious computer experts from hacking into your Facebook account. The more sophisticated the system, or the more critical, private information that system holds, the more advanced the identification system protecting it becomes.

Fingerprint scans and iris identification are just two types of authentication methods, once thought of as science fiction, that are in wide use by the most secure systems. But fingerprints can be stolen and iris scans can be replicated. Nothing has proven foolproof from being subject to computer hackers.

“The principal argument for behavioral, biometric authentication is that standard modes of authentication, like a password, authenticates you once before you access the service,” said Abdul Serwadda a cybersecurity expert and assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science at Texas Tech University.

“Now, once you’ve accessed the service, there is no other way for the system to still know it is you. The system is blind as to who is using the service. So the area of behavioral authentication looks at other user-identifying patterns that can keep the system aware of the person who is using it. Through such patterns, the system can keep track of some confidence metric about who might be using it and immediately prompt for reentry of the password whenever the confidence metric falls below a certain threshold.”

One of those patterns that is growing in popularity within the research community is the use of brain waves obtained from an electroencephalogram, or EEG. Several research groups around the country have recently showcased systems which use EEG to authenticate users with very high accuracy.

However, those brain waves can tell more about a person than just his or her identity. It could reveal medical, behavioral or emotional aspects of a person that, if brought to light, could be embarrassing or damaging to that person. And with EEG devices becoming much more affordable, accurate and portable and applications being designed that allows people to more readily read an EEG scan, the likelihood of that happening is dangerously high.

“The EEG has become a commodity application. For $100 you can buy an EEG device that fits on your head just like a pair of headphones,” Serwadda said. “Now there are apps on the market, brain-sensing apps where you can buy the gadget, download the app on your phone and begin to interact with the app using your brain signals. That led us to think; now we have these brain signals that were traditionally accessed only by doctors being handled by regular people. Now anyone who can write an app can get access to users’ brain signals and try to manipulate them to discover what is going on.”

That’s where Serwadda and graduate student Richard Matovu focused their attention: attempting to see if certain traits could be gleaned from a person’s brain waves. They presented their findings recently to the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) International Conference on Biometrics.

Brain waves and cybersecuritySerwadda said the technology is still evolving in terms of being able to use a person’s brain waves for authentication purposes. But it is a heavily researched field that has drawn the attention of several federal organizations. The National Science Foundation (NSF), funds a three-year project on which Serwadda and others from Syracuse University and the University of Alabama-Birmingham are exploring how several behavioral modalities, including EEG brain patterns, could be leveraged to augment traditional user authentication mechanisms.

“There are no installations yet, but a lot of research is going on to see if EEG patterns could be incorporated into standard behavioral authentication procedures,” Serwadda said

Assuming a system uses EEG as the modality for user authentication, typically for such a system, all variables have been optimized to maximize authentication accuracy. A selection of such variables would include:

The features used to build user templates.

The signal frequency ranges from which features are extracted.

The regions of the brain on which the electrodes are placed, among other variables.Under this assumption of a finely tuned authentication system, Serwadda and his colleagues tackled the following questions:

If a malicious entity were to somehow access templates from this authentication-optimized system, would he or she be able to exploit these templates to infer non-authentication-centric information about the users with high accuracy?

In the event that such inferences are possible, which attributes of template design could reduce or increase the threat?Turns out, they indeed found EEG authentication systems to give away non-authentication-centric information. Using an authentication system from UC-Berkeley and a variant of another from a team at Binghamton University and the University of Buffalo, Serwadda and Matovu tested their hypothesis, using alcoholism as the sensitive private information which an adversary might want to infer from EEG authentication templates.

In a study involving 25 formally diagnosed alcoholics and 25 non-alcoholic subjects, the lowest error rate obtained when identifying alcoholics was 25 percent, meaning a classification accuracy of approximately 75 percent.

When they tweaked the system and changed several variables, they found that the ability to detect alcoholic behavior could be tremendously reduced at the cost of slightly reducing the performance of the EEG authentication system.

Motivation for discovery

Serwadda’s motivation for proving brain waves could be used to reveal potentially harmful personal information wasn’t to improve the methods for obtaining that information. It’s to prevent it.

To illustrate, he gives an analogy using fingerprint identification at an airport. Fingerprint scans read ridges and valleys on the finger to determine a person’s unique identity, and that’s it.

In a hypothetical scenario where such systems could only function accurately if the user’s finger was pricked and some blood drawn from it, this would be problematic because the blood drawn by the prick could be used to infer things other than the user’s identity, such as whether a person suffers from certain diseases, such as diabetes.

Given the amount of extra information that EEG authentication systems are able glean about the user, current EEG systems could be likened to the hypothetical fingerprint reader that pricks the user’s finger. Serwadda wants to drive research that develops EEG authentication systems that perform the intended purpose while revealing minimal information about traits other than the user’s identity in authentication terms.

Currently, in the vast majority of studies on the EEG authentication problem, researchers primarily seek to outdo each other in terms of the system error rates. They work with the central objective of designing a system having error rates which are much lower than the state-of-the-art. Whenever a research group develops or publishes an EEG authentication system that attains the lowest error rates, such a system is immediately installed as the reference point.

A critical question that has not seen much attention up to this point is how certain design attributes of these systems, in other words the kinds of features used to formulate the user template, might relate to their potential to leak sensitive personal information. If, for example, a system with the lowest authentication error rates comes with the added baggage of leaking a significantly higher amount of private information, then such a system might, in practice, not be as useful as its low error rates suggest. Users would only accept, and get the full utility of the system, if the potential privacy breaches associated with the system are well understood and appropriate mitigations undertaken.

But, Serwadda said, while the EEG is still being studied, the next wave of invention is already beginning.

“In light of the privacy challenges seen with the EEG, it is noteworthy that the next wave of technology after the EEG is already being developed,” Serwadda said. “One of those technologies is functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), which has a much higher signal-to-noise ratio than an EEG. It gives a more accurate picture of brain activity given its ability to focus on a particular region of the brain.”

The good news, for now, is fNIRS technology is still quite expensive; however there is every likelihood that the prices will drop over time, potentially leading to a civilian application to this technology. Thanks to the efforts of researchers like Serwadda, minimizing the leakage of sensitive personal information through these technologies is beginning to gain attention in the research community.

“The basic idea behind this research is to motivate a direction of research which selects design parameters in such a way that we not only care about recognizing users very accurately but also care about minimizing the amount of sensitive personal information it can read,” Serwadda said.

Read the original article here

- Comments (0)

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS

Subscribe to our Feed via RSS